All allergic diseases including asthma, rhinitis, sinusitis, and anaphylaxis are the result of the mobilization of the immune system in response to a foreign substance in the body.

In order to first develop allergies, the body must be exposed to something in the environment that prompts it to initiate an immune response. These foreign substances, called allergens, can be something we have swallowed, something we have inhaled, something we have touched, or something injected into us like a needle or an insect sting.

When an allergen enters our body, a person with an inherited predisposition to this allergen will begin to develop a specific type of antibody called immunoglobin E (IgE). An antibody is a protein produced by our immune system, which circulate in the bloodstream and help to remove any substances or organisms, such as bacteria or viruses, which has invaded our body. The IgE antibody is one of five different classes of antibody made by our immune system. The other four are: IgM, IgG, IgD, and IgA. IgE antibodies originally evolved to give the body a way of protecting itself from parasites. However, it is also specifically targeted at allergens.

Although everyone makes IgE, people whom are prone to allergic reactions make much larger quantities. Inheritance has a major influence on allergies. Inheritance determines whether or not a person makes IgE in response to everyday substances. Although it is unlikely that there’s a single gene behind allergies in all allergic individuals, you are still more likely to have allergies if other members of your family have them. Researchers say that if you have 1 sibling with allergies, you have a 33% chance of having them. If you have 1 parent that is allergic, you have a 50% chance, and if you have 2 parents with allergies, you have a 75-80% chance of being allergic. Other influences such as viral infections, smoking, and hormones can also determine whether one develops allergies.

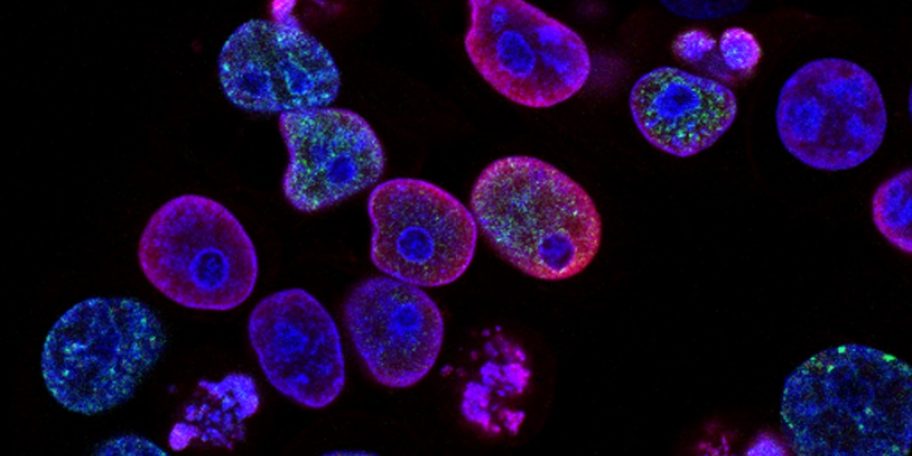

All immunoglobins including IgE are made by B-lymphocytes, a specific type of white blood cell. The B-lymphocyte’s antibody production is regulated by Helper T-lymphocytes, another type of white blood cell. In addition, macrophages, cells that ingest pieces of foreign substances, assist T-lymphocytes to prompt B-lymphocytes to make more IgE.

When an allergic individual is exposed to a sensitizing allergen, the body makes a specific IgE, one that is able to recognize only that allergen. (see above chart)

Millions of mast cells and basophils are all over the body.

Mast cells reside in tissues in the body, and basophils are in the blood stream. Both mast cells and basophils have over 100,000 receptors that are specific for the IgE antibody. When an allergen (antigen) enters the immune system, the antigen binds to these IgE receptors on the surface of the cells. When the allergic individual is reexposed to the same allergen that initiated the response, the IgE is able to bind to that allergen. When two IgE antibodies next to each other bind to the antigen, this interaction “wiggles” the membrane and causes the degranulation of the mast cell or basophil. Degranulation means the breaking down of the mast cell or basophil.

As degranulation occurs, it causes the mast cell or basophil to release a series of chemicals that orchestrate the allergic reaction. Within every mast cell or basophil are 500 to 1500 granules containing more than thirty different allergy-causing chemicals. The best known chemical that is released is histamine. Histamine causes itching if released in the skin, wheezing if released in the lung, and contributes to a loss of blood pressure if released throughout the body.

Leukotrienes are also released, and they act similar to histamines. Cytokines are also released, and one of the cytokines released by the basophil is interleukin-4, which is believed to be responsible for telling the body to make more IgE. (See Allergic Rhinitis for effects of allergy causing chemicals on the body). The intensity of this immune response is one of the many reasons that antihistamines alone do not work for most allergic disease.

The phases of an immune response

Once the mast cells and/or basophils have released their chemicals, the allergic reaction occurs rather quickly. This part of the reaction is called the immediate reaction. However, some people also experience what is called a late phase reaction. The tissues in which mast cells have released their chemicals may become hot, tender, red and swollen for several hours. The mast cells create this reaction by releasing chemicals, called chemotactic factors, that then attract many other inflammatory cells to the site. These cells include: eosinophils, neutrophils, and lymphocytes. Once they’ve arrived, each one of these cells contributes to the late phase of the allergic response. Eosinophils generate chemicals similar to those made by mast cells, as well as release more generally toxic substances that irritate the body. Neutrophils release a number of chemicals including enzymes, which degrade proteins, and in turn cause further tissue damage.

The immediate and late phase reactions together combine to form a severe allergic response.

In skin reactions, the immediate phase consists of a pale central area surrounded by redness and swelling. This response reaches its peak at about 15 minutes and goes away after about 90 minutes. However, the immediate response can also merge with the late phase that can last up to 24 hours.

In the nose, the immediate response consists of sneezing, itching, and the production of nasal secretions. The late phase response is associated with swelling, constant blockage of the nasal passages, and continuous mucus production.

In the lung, the immediate response begins within minutes or even seconds after exposure to an allergen. This includes shortness of breath, wheezing, and coughing. This disappears after an hour or so. Three to four hours later, the late phase reaction begins. It is also characterized by shortness of breath and coughing, and can last up to 24 hours.

If the allergic response sounds very confusing, you’re right!!! That is why it is so difficult to treat allergies with a single medication. The immune response is an endless cycle that constantly produces IgE antibodies and other chemicals, and therefore causes continuing allergic symptoms. At this time, we cannot cure allergies, we can only hope to contain them. Due to the complexity of the allergic cascade multiple drugs are often needed to control symptoms. Alternatives including allergy desensitization shots which reduce the overall reactivity of the immune system may be explored with your doctor.